As it turned out, the second half of our life together is a bit short on the gentleness we dreamed of and a bit long on suffering. Karl would be the first to admit that we were often despairing, dispirited, broken, and broke. Despite our blissful and courageous beginning, our relationship is a rocky ride, smoothed by a great, trusting love.

Four years into our marriage, Karl comes precariously close to dying of despair. His childhood wounds catch up with him: multiple abandonments, leading to a loss of self-worth and a fear of failure. The smallest boy in his class, he’d learned to be tough to handle bullying in the children’s home. Later he becomes a skilled lightweight boxer in an Australian travelling circus. Now he is struggling (as a social work student at Sydney University) to allow his softer, gentler side to emerge.

I handle Karl’s depression poorly, misjudging his emotional fragility.

One evening in November 1998, returning home to our terrace house in Glebe, Sydney, I smell gas. As I tear open the front door, I can see through to the kitchen. Karl is sprawled on the floor, his head in the oven. He blessedly failed to discover that poison was removed from Sydney’s domestic gas supply decades earlier. He has finished off a bottle of vodka and pretty much knocked himself out. But he is alive. I slap his face until he comes to.

He screams at me (Oh fuck, oh fuck!), jumps up, crashes through the back door, scales the two-meter back fence and runs away, returning sheepishly an hour later. After a few days in a hospital psychiatric ward, he is released into my care. “Keep a close eye on him,” Dr. Wong, the hospital psychiatrist warns me.

“What on earth does that mean?” I retort.

“He’ll try it again. They always do,” is all he can tell me.

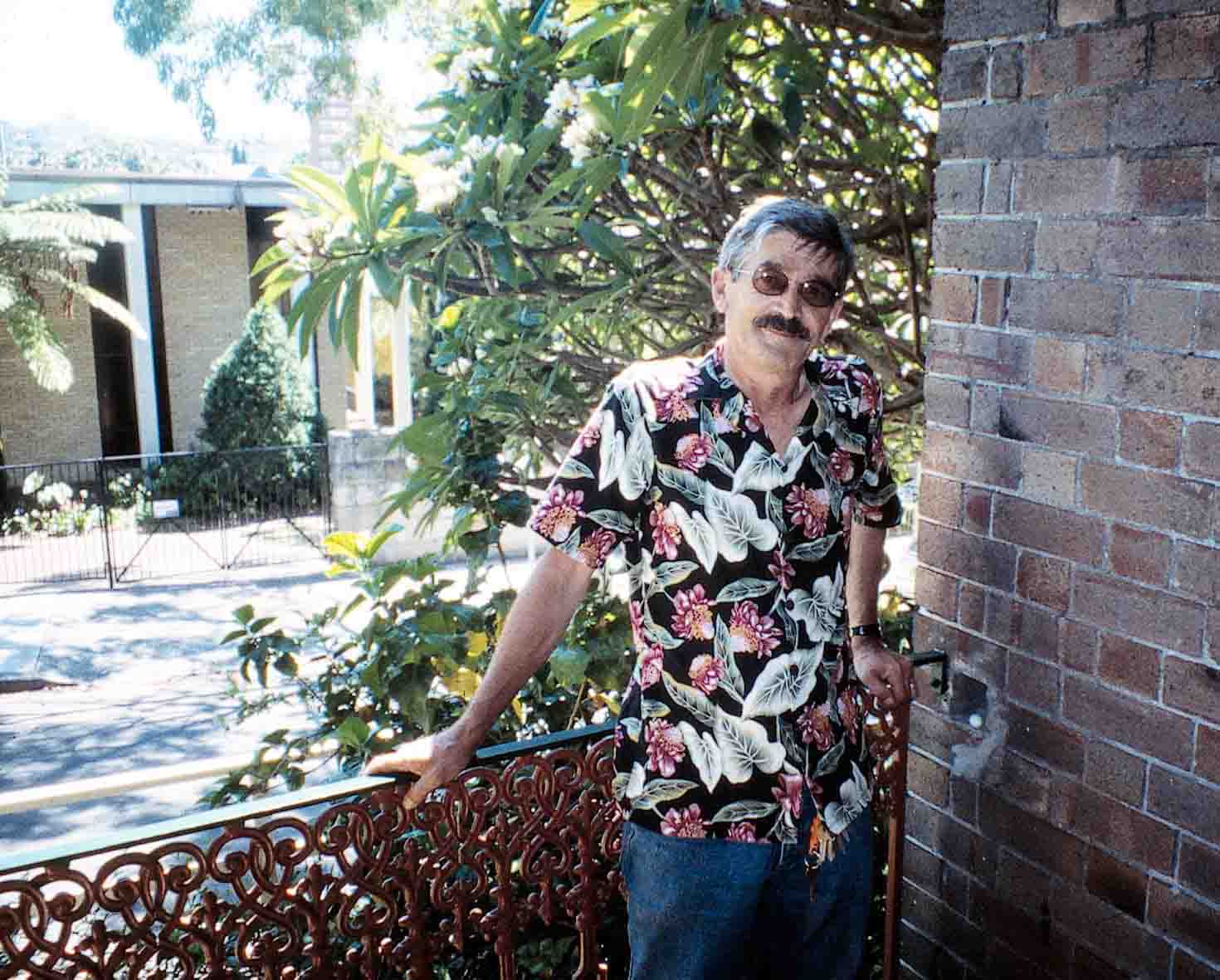

Now I can see a wistful look in Karl’s eyes in this photograph taken at our Glebe house at that time. He was falling apart. And I cannot not see it then.

“Karl’s candle could easily be extinguished.”

Following Karl’s suicide attempt, I am terrified, desperate, furious, and at the end of my tether. It is a dark time in our relationship. A clairvoyant friend tells me at the end of 1998 — our most terrible year — that “Karl’s candle could easily be extinguished.” I live in constant terror that he will kill himself.

And later, I live with another sort of fear: that he’ll be lost to me somehow. I do not know how that will happen. I just have a premonition.

Premonition

I know, at some level, that Karl will not live to be an old-old man. He will not make old bones. With Karl, life always is about carpe diem. My premonitions continue. Later, in Nimbin, when I’d wake in the night, I tiptoe down the hall and stand at his bedroom door, listening for — listening to — his breathing. I do not dare voice such a terrifying possibility. But this is what I write years later in a poem called “Premonition”:

barefoot in your bedroom’s

shadowed doorway

bending in to listen

for your breathing

begging God to spare you

because I love you

because I need you

because I can’t imagine

life without you.

Gratitude

While Karl’s suicide attempt fills me with horror, I do recall one moment of gratitude I never share with him. Shortly before that painful day, our old car is stolen. The police recover it virtually unharmed some weeks later. If we had still had our car, Karl could have easily and successfully gassed himself in it.

At the time, I notice the huge blessing of the theft of our car. I experience a powerful sense of grace. But for both our sakes, I decide we must move from Sydney immediately. I can no longer live in our Glebe house. I cannot face the kitchen or even the front door. Every time I open it and glance into the kitchen, my mind flashes to the image of Karl with his head in the oven.

So I quit my university teaching job. I feel I am saving both of our lives – and maybe our marriage – by moving us to Brisbane. I have only two close friends in Brisbane (Andrew and Geoffrey), but I am saving Karl’s life.

Healing in Brisbane

In Brisbane’s sunny climate, our broken relationship heals. Mostly.

Karl heals. Mostly.

Eventually, after several verbal (but not actual) suicide threats, Karl apologizes and swears never to do such a stupid thing again. We put things back together.

Shortly after his breakdown, feeling stronger, Karl tells me, “I have undergone a profound period of change since you and I declared our mutual love and commitment to share life’s journey together.”

He declares that my love and encouragement have enabled him to scale heights previously unimagined. “Without your guidance,” he continues, “I doubt that I would have had the courage to embark on such a different life.”

The irony of this poignant declaration is that, while I often lecture Karl about relationships, I am the one who is learning about courage, as I witness him bravely confronting what he called his “items” and entering into professional and social realms vastly different from anything he had known.

A few months later, in early 1999, Karl again explains that I had given him courage! However, he confides, “You have shown me so many new horizons and have contributed so much that now I am afraid of failure and of being unworthy.”

In 2002, he writes to me: “You are capable of singing to my soul and touching my innermost self with the warmth you generate in me.”

A powerful lesson

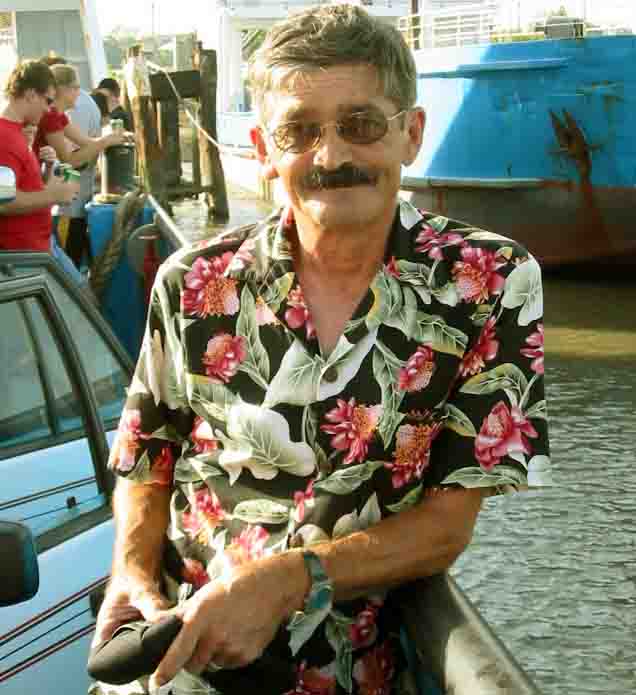

Karl’s tender openness reveals a powerful lesson, reminding us both that what might seem like a simple act — loving yourself — demands the most exceptional courage, an act of courage unlike any other. I recognize that Karl — like me — carries a burden of trauma into our late-in-life marriage. He has many of the qualities of an institutionalized person, as he spent much of his childhood in an institution. When I bring back a beautiful shirt from a trip to Hawai‘i, he hides it. When pressed, he explains that in the children’s home in Bavaria (where he lived from age ten to 14), nobody had their own clothes.

Some old habits were hard to break.