Man who finishes house dies

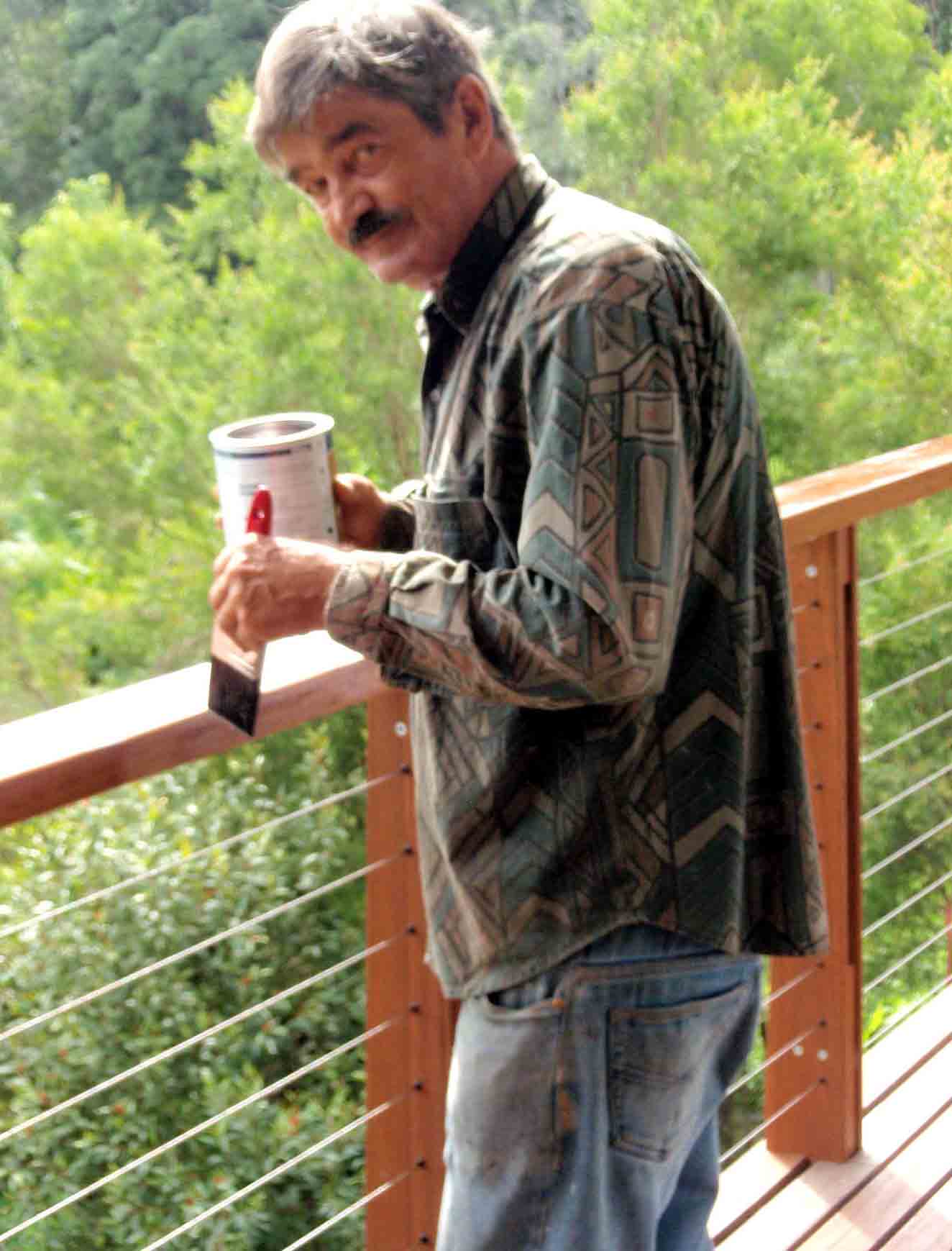

In Nimbin, Karl is not the depressed or distracted person he sometimes is in the city. He has landed. More than that, after decades of wandering, he has found his tribe, his people, and his community. And now, after nearly 10 years together, Karl can make a home with me. And for me.

And I am eager to progress the house building. I privately develop advance my new theory (I’d read somewhere that this was a Chinese or Indian proverb): Man who finishes house dies. I figure that if I could keep Karl busy building and landscaping our half-acre site (in other words, never finishing the house), his depression and suicidal thoughts might fade, he’ll be less drug-dependent, and he will grow into a happy “little old guy” with whom I can share my sunset years. I am on a mission: saving Karl’s life. For me, the Nimbin adventure begins as a “life-or-death” exercise.

Claire

In 2003, I identify a young architecture student working part-time in our Brisbane office as the designer of our new house, despite her reluctance. Claire always claims that she didn’t know how to do it, and I always counter that she is brilliant and, of course, she does know how to do it. We are both right: Claire is not entirely qualified and has yet to study construction, costings, and specifications. She bases her design on my brief, which, while comprehensive, was expensive to build. The local builders sneer at our sketchy, basic drawings, but I know that they promise a beautiful, functional rural house. And I am right.

Karl loved Claire and easily identified and celebrated both her talent and her courage. I never heard a critical word from him about her house design. This video from January 2005 shows the two of them inspecting the house site. You can see the comfortable way that they related to each other:

Click here

Dreaming our house is almost as joyful as actually building it and living in it. We live in the finished house for fewer than five years, but we dream it for fifteen. I develop a set of poetic design patterns that captured my intentions. They include everything from a stargazing balcony to a one-person kitchen where the cook could converse with his guests while he cooked, and they relaxed on the spacious back deck. We fail to achieve only one of our 55 patterns: a private, sacred space for Karl. I often wonder why that is.

Mark van Norman

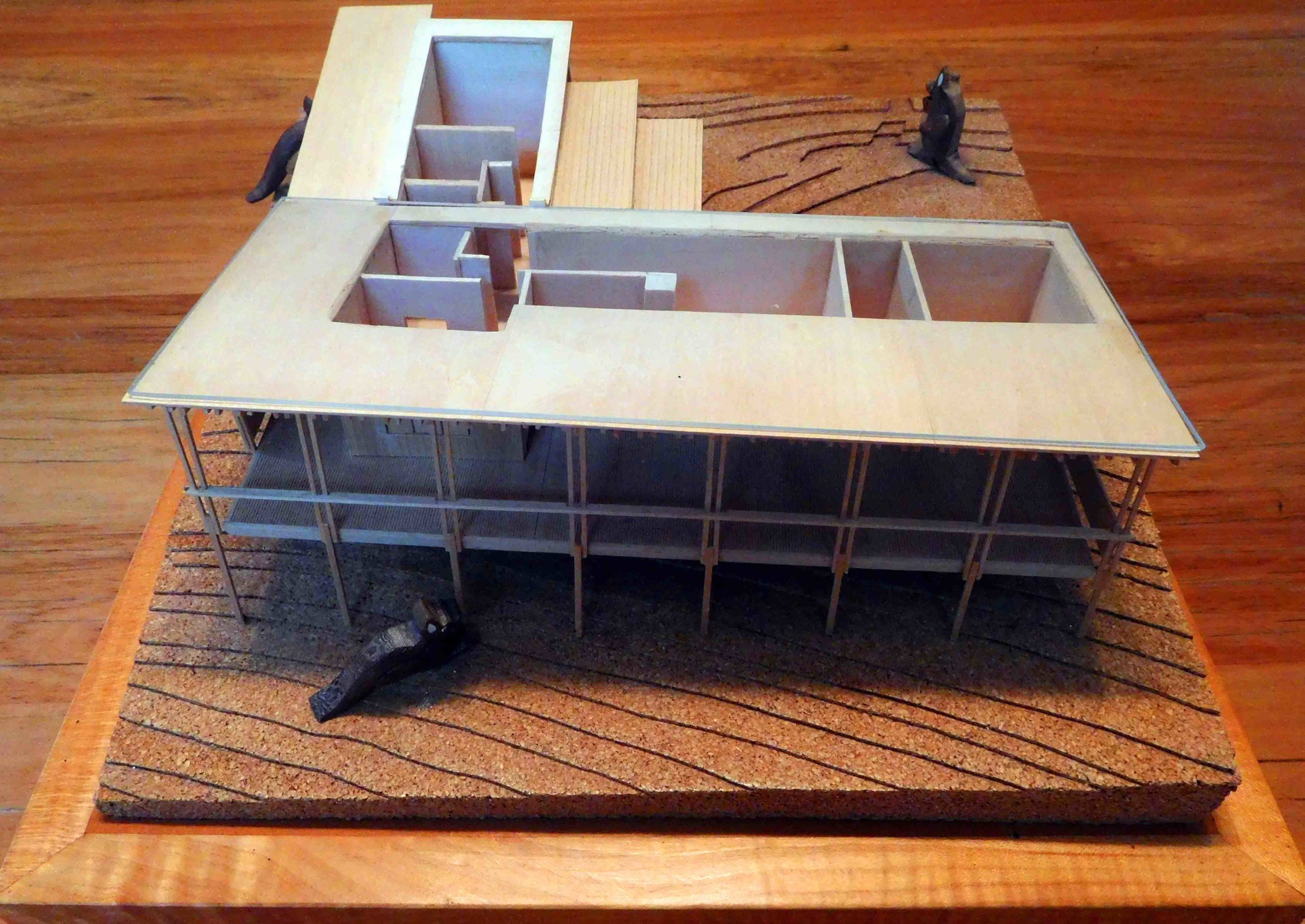

In 2013, my dear friend, California-based architect and artist, Mark van Norman, spends 350 hours creating a scale model of our house as a 65th birthday gift for Karl. Mark has never seen the real house, so he creates his model from photographs and plans. The gigantic wallabies are the closest to scale that we can find!

This precious gift holds pride of place in our hallway and Karl is hugely impressed by it — and Mark’s generosity and skill.

Roughing it

The madcap way our Nimbin house takes shape bewilders our urban, professional friends. Once, we even put out a call for donations to finish the roof during the wettest Nimbin winter on record. Nevertheless, we quickly learn to adapt. As he is a qualified welder-boilermaker, Karl is comfortable working with other trades. And he has wily ways. When the man from the telephone company arrives to install the Internet and telephone line to our makeshift tent (the hootchie), he asks Karl if there would soon be a house there.

“Of course!” Karl exclaims.

The phone line was connected to the tent, and a house was built there eventually — it just took another 10 years.

OUR RURAL ADVENTURE

Thus begins our rural adventure. First, mostly on weekends, we live in a tent, then in a large, tent-like structure that Karl built ( “the hootchie”), later in a metal shed, and then, from about 2009, in parts of the partly built house. Like most rural folk, we lack the funds to begin building. So, like most rural folk, we start anyway. We cobble together the money we have, helped by an unexpected inheritance from an elderly aunt — and begin building our rural dream.

The hootchie

We love living in our first Nimbin home: the hootchie: a makeshift tent-like structure. Karl builds it from star pickets, flexible plumbing hose, tarpaulins and a lot of wire. It is weatherproof and flexible. I cry when we have to demolish the hootchie to make way for “progress”.

Often, on a Saturday morning (having arrived late the night before after driving for two hours from Brisbane), the laughter of kookaburras in a nearby tree wakes me in the hootchie, where I lie under my mosquito net. I find that Karl had already departed – for his café in the Village and his delights: a black coffee, the weekend newspapers, the crossword, and maybe a game of dominoes with his new friends.

I make a cup of tea on the camping stove and sit in my folding chair for hours, gazing at the silhouette of Blue Knob in the distance. I pack a briefcase full of work on Friday afternoons, but I rarely open it. I just sit there and soak up the beautiful landscape and dream of our new home. And our new rural life.

The beauty of winter mornings with fog in the valley makes me weep for joy!

Those weekends, for a few years before any real physical work began on the house site, are absolute bliss for both of us. Life in Nimbin is peaceful and simple. After we close the Brisbane office and sell our city apartment, we move permanently to Nimbin, trading in the hootchie for a metal shed that Karl builds. For many years, we live without a toilet or running water; then, we have a hose connected to a small rainwater tank. And a pit toilet. Or a 50-meter hike to the community toilet up the road. I like my creature comforts, and I find that part quite tricky, particularly in the rain.

The shed

The shed

Steph Vajda and Karl building the shed, September 2005

In 2006, Lismore City Council approves our house plans, and we begin building our house. A short time later, to promote my professional work, I co-author three professional books. Sadly, the publisher (Earthscan) is taken over, and all my marketing plans collapse. We sink into debt. By 2011, although the inheritance enables us to finish most of the house, we are teetering on the edge of insolvency.

Our eco-house absorbs all our funds.

Chop, chop, stir, stir

I cherish a vivid recollection of Karl standing in his partly built kitchen, while I guide him to visualize the pleasures of eventually cooking there. He obediently role-plays with gestures and appropriate sounds: “Chop, chop, stir, stir.” It is a powerful statement of intent.

Eventually, Karl does spend several years delightedly chopping and stirring in his beautiful modern kitchen.

That is his greatest pleasure.

Karl selecting a pan, 2010

The completed kitchen 2016 Photo: Denny Thornborough

Mark van Norman’s beautiful artwork can be seen here: http://www.smallobjects.net