Chapter 1: Losing Karl

The loneliest wave of loss is the one that carries a loved one away towards death.

— John O’Donohue, Eternal Echoes, 1999: 241.

6 FEBRUARY 2016: On the Kyogle Road, Uki, New South Wales, Australia

“Too fast!

Oh, God! That white post’s awfully close to the car. Oh, too fast, too fast!”

Smash.

Gliding, floating, flying…

Thud.

Blackness.

A pulse of electric blue light.

I come to my senses in the cool, dark water of a muddy river eddy, water rising quickly, alarmingly outside the submerged car, rushing through one open window.

Late afternoon summer light is slanting in from above.

After seconds that seem like hours, I manage to work out how to locate the buckle and unfasten my seat belt. Now I’m upright in the upside-down car, sitting on the roof with water to my chin. A pocket of air above, the floor above that.

Somehow, I’ve landed in the back of the car, facing my Beloved’s back. My airbag must have thrown me there. He’s in the front, tangled in his seat belt.

***

I remember fragments of my last words to him in the car: “Oh, sweetie, thank you for the beautiful birthday lunch with our friends. Thank you for loving me for the past 23 years. I love you so much, Beloved.”

I reach my right hand to pat his knee.

“Thank you. I’m so glad that made you happy. I love you too, Wadie” is his delighted response, as he navigates the tight curves of the narrow, slippery rural road.

***

Now, in the back of the car, I have some air. I am breathing, and my heart is beating. My eyes can see, but only dimly.

The front of the car has no air.

After skidding across the road, it has tumbled a hundred feet into the river, landing off-balance on its roof, the front fully submerged.

Karl is sitting up, silhouetted in water as dark as chocolate milk. Once I’m free of my seatbelt, I make several desperate attempts, but I cannot untangle him. His swimming hands gently describe small circles around his body. Maybe he’s reaching for me. Or maybe he’s unconscious, and the current is moving his hands. I reach forward and grasp one circling hand with my left hand.

Then I hear a shocking gurgle of water, like a large sink emptying, as river water fills Karl’s lungs. His head flops to one side. In seconds, he moves from life to lifelessness.

My Beloved drowns before me.

Karl breathes his last breath into the river. This sacred river, source of life for so many beings, extinguishes his life.

Karl! Hold your head up!

I never call him Karl. Except in emergencies. Only “My Beloved”.

Screaming at my Beloved, only inches from me.

Screaming again: “Karl! Hold your head up!”

Is this it, then?

The end of all our dreams? Head to one side, lifeless?

My Romani husband hated water. Our honeymoon was the only time I saw him anywhere near it when we shared a celebratory swim.

“It is in the tradition of Romani people to avoid water,” he’d repeatedly declare, explaining that for centuries, members of authentic Romani communities avoided water as a gesture of freedom from oppressive bourgeois standards.

Is this the death we fear?

I’m frantic now. My mind is racing. The water’s still rising. It’s rising above my chin. I spin around, grabbing for all the doors handles, but the doors are firmly stuck.

Karl has powerful talents, I remember. Maybe he has one spell left? Could his unique Romani magic defy natural laws, hex them? We are in an ancient, forgiving river, after all. In a spiritual center. All we need is one small miracle.

I scream again: “Karl! Hold your head up!”

Screaming at a dead man.

Silence now: car, river, the Gypsy, and me. Water rising around and within us.

I will not die in this river.

I take a last look at my Beloved, now collapsed forward. Then I dive down to reach the open window on my side of the car. I slide through it, imagining I’ll need powerful strokes to reach the surface. I forget to hold my breath, taste muddy water, swallow, and splutter. Choking and gasping, I open my eyes, astonished to find myself standing in only a few feet of water.

I look up to see people are crowding the narrow roadside above me.

“He’s drowning!” I scream at them.

“Help us! Help us!”

I scream. I scream again.

Trembling, barefoot, stumbling on the sharp river stones, I observe a surreal tableau of airbags, shopping bags, and roadmaps floating slowly through the hatch door, heading gently downstream, responding to the pull of the ocean. I reach for a shopping bag and stop. How ridiculous!

Then I turn to see two men — later known to me as Rob and Ben — scrambling down the steep, slippery, reedy bank.

“Help him, help him,” I scream at them. “He’s trapped inside. Please help him!”

Rob tries all the doors, but they are centrally locked. Ben wrenches a massive stone from the river bank and smashes the back window on Karl’s side. After several unsuccessful attempts, Rob pushes his head into a pocket of air, dives into the muddy water, and feels for the front door lock. He unlocks the front door. Then Ben pulls it open, untangles Karl from his seatbelt, and hauls his lifeless body through the door.

They drag Karl from the river and prop him up on the bank.

I stand alone in the river. Nobody approaches me.

I witness and pray. But nobody can reverse the natural order of things. When several attempts at CPR by Rob and a police officer fail, another police officer announces, first to others: “There’s no pulse”.

Then he turns to look down at me and proclaims: “Madam, I regret to inform you that your husband is deceased”.

I stand alone in the river.

On the roadside above, swarming with emergency vehicles and personnel, it’s all about me: the survivor. But I can’t allow my focus to shift. I cannot leave Karl now. I have work to do.

I stumble to the shore of life. I am broken; I have nothing left to lose.

I stand alone in the river.

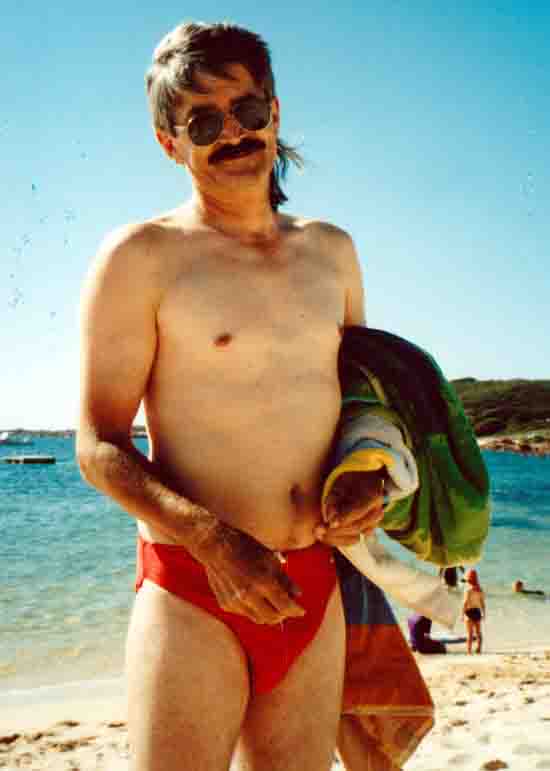

Before me, almost vertical on the reedy bank, illuminated by light through the white gums, lies my soul partner of 23 years. Tanned and lean, in full Gypsy gear: black shirt, striped black trousers, and new blue suspenders donned to celebrate my birthday. Black patent shoes I’d polished that morning.

Karl doesn’t look dead or drowned. He looks like he’s resting, getting ready to party.

So beautiful, so beautifully turned out.

(In our shabby, unkempt, hippie village, Nimbin locals would ask a well-dressed neighbor: “Is it a court appearance or a funeral you’re off to today, mate?”)

My Beloved is dressed for his own funeral.

His lips are slightly parted. Maybe had one more thing to say.

His eyes are partly closed, as though he cannot admit the light from above.

All eyes are on Karl — and on me.

I stand alone in the river, witnessing, as Karl gently gives his life back to God. I sense his soul leaving his body.

What care can I offer now?

How can I ease his pain and smooth his passage?

We’re cradled in Nature’s depths — in a shallow lagoon of a sacred, meandering, shallow river. Embraced by rainforest, we’re circled by human caring. Night birds gather in the top branches of the tallest gums, witnessing, as a pale twilight descends.

What can I offer?

I remember my sacred promise to Gaia, the Earth Goddess. I am in Her service. I remember why.

The world pauses.

I do my simple best.

The water’s cool balm comforts me as I bend forward. My hand extends only to Karl’s feet; I can reach no further. Balancing my left hand against the bank and my torn feet on riverbed rocks, I gently place my right hand under the soles of his feet.

Then I beg Gaia, the Earth Goddess and my protector, to watch over and guide my precious love, now lost to this material life. I invoke Her healing powers. I follow Her guidance, drawing energy from deep below the riverbed, up through my body. I transmute that raw energy into love in my heart. Then I transmit that love energy through my right hand. It electrifies my hand as it reaches Karl.

He accepts, drawing energy from me.

Gaia introduced us. Now she witnesses our earthly severance.

Husband and wife, frozen in time, we share our last moments of sacred belonging.

I release Karl with my whispered blessing:

Oh, Beloved, I know you are not afraid to die. You have always said yes to life, and you have died as you lived. This must be your time. Please hear me: now you can let go and be free of your body. Please do not be afraid to let go of me. I will not hold you back.

I withdraw my hand, my task complete.

It’s over.

The world resumes.

Five men struggle for footholds on the steep, slippery river bank. They steady a long metal ladder. I lift a bleeding foot onto the first rung. It’s cold. I grab onto it and glance back, terrified I’ll lose my grip and tumble backward.

I will not die in this river.

Partway up the ladder, I stop and bend to gaze again into the face of the man I love. I imprint this picture on my mind: my last glimpse of my beloved Karl. I steady myself on the ladder and reach my right hand to touch his wrist.

It’s still warm. Karl is crossing the threshold.

“Love you with all my heart, Beloved. You will live in my heart forever,” I whisper.

Firetrucks, ambulances, police cars, and tow trucks crowd the narrow road above me. Red and blue lights are flashing. Small groups of people, including police and emergency services personnel, are conferring. Light rain is falling.

A fireman grabs my arm as I reach the road’s edge. Then I stand alone, renegotiating my balance with the Earth. I bend over, vomiting river water, then I wait to be loaded into an ambulance.

To my right, I notice Rob Brims, surrounded by police, wrapped in a ragged towel, also bent over, shivering, sobbing. Dear sweet man. He risked his life, trying to save my Beloved. I stumble across and speak to him. Thank him. Ask him to thank his friend. I mumble some words: I don’t know what.

Inside the ambulance, John, in a yellow fluoro jacket, smiles at me. He is wielding a formidable pair of scissors, huge like gardening shears.

“I am going to cut off your dress, now, madam,” he announces.

I cough.

“John, this is my new dress, and today was my birthday party,” I whisper.

“Could you just pull it over my head, please?” He does that.

“Now I am going to cut off your tights, madam,” he says.

“John,” I beg, “Please call me Wendy. I am just Wendy. I do not want to be difficult. They only cost eight dollars, these tights. But it’s a 70-kilometer round-trip to K-Mart from my place. Do you think you could just pull them off, please?”

John pulls off my tights, and I let him cut off my underwear. Then he gives me a tetanus shot, fastens the neck brace, and settles me on the stretcher. We tear up the winding road to the Tweed Heads Memorial Hospital, siren blaring, lights flashing.