Sall acts of love

Anyone who is mourning can benefit equally from small, symbolic acts of love that provide get-through-the-day meaning and comfort. Before the Nimbin property sold and I moved away, I am comforted by tending Karl’s flower garden and making the repairs he would have made.

Karl adored our friend, Rose. After I move into her Brisbane house, I relish mixing paint colors and painting the inside of her shed in what I know are her favorite pastel “Sufi” colors, while composing new songs and singing them to Karl. I feel that Karl and I painted Rose’s shed together.

Triny, who owns a rural property in Nimbin, digs stones from her land to mark the borders of Karl’s grave. She regularly weeds it and sends photos to show how the plants are flourishing.

Steph finds and painted a beautiful piece of sandstone for Karl’s gravestone. Rose laboriously cements it into the ground, planted sturdy plants, and waters and tends his gravesite for many months.

In November 2017, Rose and I dig in another plant and cement dozens of brightly colored stones beside the gravestone.

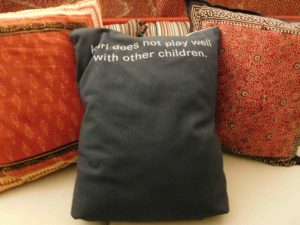

Rose and Lee-Anne sews cushion covers from two of Karl’s favorite Hawai‘ian shirts for my bed. Another cushion cover made by Rose Gardener warns, “Karl did not play well with other children.” She sews it from a t-shirt I had made for him as a Christmas gift.

Spiritual connection as “Post-Traumatic Growth”

Grieving people ache for connection with the one they have lost. Our deep yearning is nothing less than spiritual yearning – to bridge the gap between the living and the dead. We may find meaning and benefits in surprising places. My friends smile as I enumerate the many benefits nested in what seems to be such a tragic situation (like the flash flood in Rose’s house in early 2017). It is not our loss, but our struggle with the loss and our search for meaning that can lead to what is now called “Post-Traumatic Growth” (PTG): positive psychological change we experience when we struggle with (and eventually accept) a highly challenging, stressful, and traumatic event.

Sense of PRESENCE and anomalous or extraordinary experiences

Reading the psychological research on bereavement, I observe a shift in mainstream psychologists’ attitudes that parallels the change regarding the value of continuing bonds. Some researchers now accept that continuing relationships with loved ones can be “spiritually understood”, can help us resolve feelings of hopelessness, and can even be a catalyst for PTG. Extraordinary or anomalous experiences or “presences” (a glimpse of the person in a mirror, the smell of their tobacco, a sense of presence that we cannot explain, even music, tapping, or voices) might pose challenges as we try to integrate them into our worldview.

Widely accepted in so-called spiritual and spiritualist circles, they include everything from vivid imagery to finding a feather on your path. They often occur following a sudden or untimely death. They can be seen as offering a hopeful resolution to feelings of hopelessness by substituting communication for isolation. These experiences tend to be consoling and hopeful, offering release. To me, this evidence feels comforting and reassuring.

In my case, every time a friend or relative dies, the electrical system of my home acts up for days. When my brother-in-law Graham (an industrial arts teacher) died a few years ago, three electrical circuits in our house blew in succession. Usually, for me, it’s flickering or dimming of lights, a blown light bulb, or a light that turns itself on and off without human intervention.

Could experiencing these presences be pathological?

Some mainstream psychologists are concerned that presences could be pathological. Such phenomena could pose challenges, as psychologists usually class them as “intra-psychic subjective phenomena” that should disappear as grief diminishes. However, many agree that if it is not pathological, it could lead to better coping. A 1996 study of widows shows that memories and images were a source of strength, a “safe haven” to help mend the trauma of loss, an inner voice to lessen isolation, and a reassurance of the possibility of immortality.

What researchers call “presences” can help us expand our spiritual horizons, develop a new spiritually informed sense of identity, and move on while maintaining meaning in the past. Following Karl’s death, I experience a philosophy of life that includes personal and spiritual change and growth, a sense of well-being, greater maturity, a more positive attitude toward life, diminished existential fear, and heightened existential awareness. In essence, presences help me feel connected to Karl.

After Karl’s death, I am relieved to find that most psychologists now agree that continuing bonds have many benefits. For my part, I feel consoled, supported, validated, guided, and loved. In preparing this chapter, I embark on a journey of exploration into mainstream psychological research findings to understand my natural grieving behavior, to locate it (if possible) within a conversation with a broader meaning, and to examine any aspects that might be inappropriate, dysfunctional, or even pathological. I undertake this research after 20 months of daily practice of communicating with Karl.

I stop writing to Karl and recording our conversations in early October 2017. That change is a massive shock, and I need to understand better what I have been doing, why I have been doing it and perhaps to understand why I can do it no longer in the same way. In Chapter 11, I explain why and how I came to cut the cords of communication between us. Communicating with Karl after his death opens me to experiences I could never have imagined. It comforts, softens, reassures, and heals my broken heart.

Our bond continues in a different form today. And it’s still powerful. As I invoke Karl and his guidance in less structured ways, I honor him and the many blessings I continue to experience.