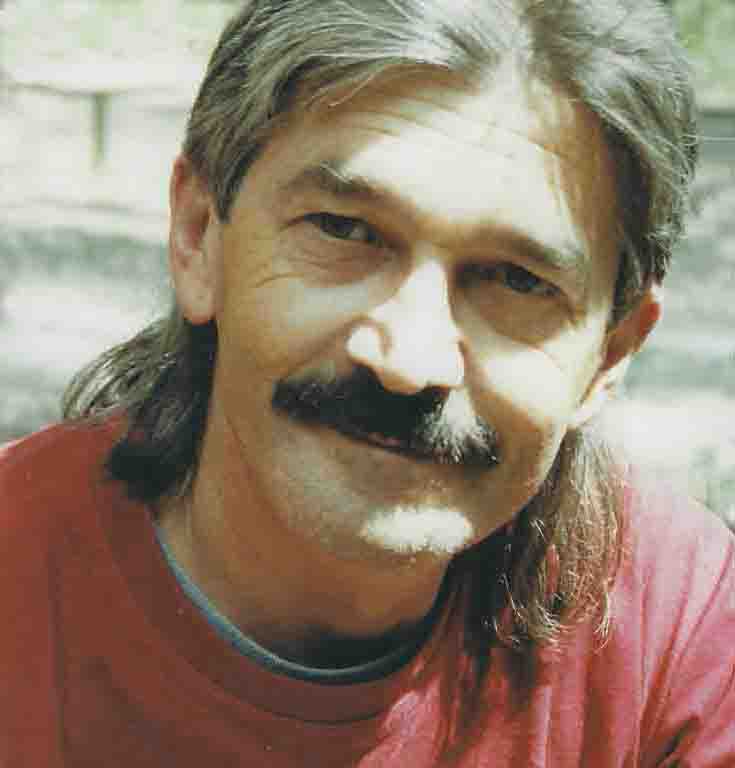

As he grew older, Karl grew more poetic.

In 2015, my Valentine’s Day card bore this inscription in his words:

LOVE

Love is a hard task, and like so many things, people misunderstand the position it has in life, often conceived as a play and a pleasure. It is, in fact, the crucial expression of our humanity. To accept the commitments we make to each other, in sickness and health, accepting the ups and downs of a long time relationship is the only path to passing the final test and preparation for the next part of our journey.

* * *

Karl was always a bit of a mystery, and even though I was curious by nature, I accepted that. Maybe I should have delved deeper. Something never felt quite right. He offered little about his previous marriage and a relationship he’d had before we met and, again, I did not question him, perhaps fearing what might accompany the opening of his emotional floodgates. I knew that his only daughter had died at birth. Those were the days when nobody in Perth hospitals knew how to manage parents’ grief. (My mother gave birth to a stillborn child in 1946 and went mad as a result.)

That heartbreaking experience, in Karl’s twenties, ended his marriage. When Karl referred to it on rare occasions, it opened up a space of such deep sadness in him that I was reluctant to enter it.

Sometimes Karl would have contact with his son, his only living child, who was born in 1978. In our early years together, I’d notice that he’d occasionally drive into Perth with more cash than usual in his pocket. Maybe to the casino, I guessed. Actually, he was meeting his teenage son and secretly giving him money to supplement his regular payments. Later, I realized that, following what was now an established family tradition going back at least three generations, Karl had pretty much abandoned this son, who’d grown up in rough circumstances.

Karl simply could not face that part of his past. When his son posted a photo of himself on Facebook standing with a rifle beside a truck loaded with dead kangaroos, Karl was shocked, as he was proud of his environmental values.

“How can he be my son?” he wailed.

Unfinished business

Karl’s relationship with his son was a tragic case of unfinished business. Initially, I was blind to that, convinced that it was not my business. But it would haunt me later when the angry and traumatized man of nearly forty turned up at his father’s memorial with his partner, his mother, and his five children. He was Karl’s son, all right: a dead ringer for Karl. He sent anguished, vulgar and furious texts to me every other day as they drove over 4500 kilometers from Perth. The men among my friends who were helping organize Karl’s memorial service shared nervous conversations about who would be “bouncers” if things got out of hand at the memorial service.

Blessedly, that did not happen. The family sat quietly together, and Karl’s son, clearly broken by anger and grief, wept throughout the service. It was heartbreaking for me to see that but, being genuinely in shock myself, I could do nothing. My friends consoled Karl’s son and his family members.

As for me: I felt it was Karl’s business, he had not attended to it, and I could not attend to it then.

However, I was not surprised to hear from Karl, in a conversation in February 2017, a year after his death:

I was brash and insensitive to my own son. I am deeply sorry about that.

“Your loving father”

A year later, sorting through the few mementos I have of Karl’s, I unearthed a remarkable treasure: a one-page letter he had written to his “dearest son”, and signed “Your loving Father, Karl.” Among other things, it said, “I love you deeply and hope that you continue to enjoy a fulfilling life.”

Karl’s relationship with his mother was another territory I avoided. On our first meeting, she took me into her kitchen, pulled up her blouse, and proudly revealed a hickey on her breast. (She was sixty.) I’d suffered decades of abuse from my mother and had finally cut off all contact. I was a motherless child, abused, bullied, rejected, invaded, and emotionally abandoned. That was enough for me. So I kept a polite distance from this mother.

Childhood abuse

One sad day, 10 years into our marriage, I told Karl that I had finally confronted with a therapist the abuse I’d suffered at my mother’s hands. Karl blurted out that he’d had a similar experience with his mother. Mired in my grief and pain, I was not remotely interested — or in any way supportive. Not even curious. I shut him down. Later, I felt uncomfortable about revisiting such a sensitive subject. Having abandoned her child as an infant, Karl’s mother, at 33, did not know how to relate to a gritty, independent 17-year-old. Karl was confused and ashamed, from the little he told me. I could only imagine how confusing — and ultimately devastating — that experience would have been for him.